Federal Reserve policy and mortgage rate cycles

In much of its history, the Federal Reserve has preferred to use its traditional tools to manipulate interest rates and help to speed up or slow down the economy. Over the last two Fed cycles, the central bank has employed some novel approaches to manipulate long-term interest rates and mortgage rates more directly. Novel monetary policies have been designed to directly influence long-term bond yields and these in turn influence long-term fixed mortgage rates. We'll first look at the Fed's novel approaches.

In much of its history, the Federal Reserve has preferred to use its traditional tools to manipulate interest rates and help to speed up or slow down the economy. Over the last two Fed cycles, the central bank has employed some novel approaches to manipulate long-term interest rates and mortgage rates more directly. Novel monetary policies have been designed to directly influence long-term bond yields and these in turn influence long-term fixed mortgage rates. We'll first look at the Fed's novel approaches.

Novel monetary policy: QE programs, 2008-2019

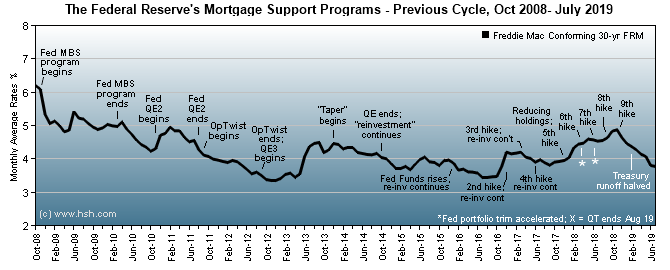

Back in 2008, with financial markets seizing up, the Fed began a then-novel approach to manipulating markets, conducting what it called "Large-Scale Asset Purchases" (LSAP), also known as Quantitative Easing (QE). In varying amounts, and in varying programs of varying size and varying duration, the Fed accumulated a lot of Treasury and mortgage bonds to help keep long-term interest rates low and to keep mortgage and Treasury markets liquid. These programs of course had an effect on mortgage rates and availability while they ran, ensuring there was always a ready buyer at any price or yield for these instruments, even if investors shunned them.

The Fed's first set of QE programs came to an end in October 2014. In general, these worked as intended, keeping long-term interest rates low through the purchase of Treasury bonds and to keep mortgage credit flowing at low rates though the purchase of agency-issued Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS). These first QE programs resulted in long-term bond yields and mortgage rates hitting then-record lows in 2012.

When the first QE programs came to a close, purchases of these instruments had expanded the Fed's holdings (it's "balance sheet") to about $4.2 trillion. Although the process of expanding its portfolio was complete, the Fed continued to "recycle" inbound cash proceeds from Treasuries and mortgages that were paid down, paid off or refinanced. As such, the Fed's "reinvestment" continued to directly influence longer-term market interest rates even after they stopped expanding to their holdings, keeping the size of their balance sheet level.

This reinvestment process was expected to end when the Fed lifted short-term interest rates at the start of a new upcycle for monetary policy. The first such increase after the Great Recession came in December 2015, but the Fed instead decided to continue its reinvestment policy for several more years, pledging to stop when "normalization of the level of the federal funds rate is well under way." A plan to begin to taper reinvestment to zero in a measured fashion was announced in June 2017, and the Fed would begin to retire some of its holdings and begin the process of shrinking its balance sheet starting in October 2017.

To gradually reduce its holdings, inbound funds being used to purchase of new Treasury bonds ware pulled back by $6 billion per month and MBS and agency bonds were trimmed by $4 billion per month. After 3 months (starting January 2018), the $6 billion and $4B reductions turned into $12 billion and $8B respectively; come April 2018, this rose to $18B and $12B and in October 2018 ended up at as $30B in reduction in Treasury holdings and $20B of mortgage-related debt being retired each month.

At its outset, the process of reducing the Fed's holdings was expected to continue for a lengthy but indeterminate period of time, with balances being steadily reduced until the Fed was comfortable that its portfolio had been trimmed to a size needed only to effectively manage monetary policy.

Just two years into a "runoff" process that was expected to continue for perhaps 3 or 4 years if not longer, the Fed changed its plans. At this time, the central bank expected to conduct monetary policy solely using its so-called "administered rates" (federal funds, interest on reserves it holds for banks, etc.), but it would to be doing so in a climate where banks would be holding an "ample supply of reserves". Large bank reserve positions mean that the Fed also needs to maintain a large portfolio in order to ensure that the federal funds target can be maintained in all market conditions.

Over the two-year period of reducing its holdings, the Fed had been draining funds from the financial system; in turn, financial conditions had begun to tighten more than expected, signaling that the balance sheet had shrunk past its optimal size. To address this, the Fed began to wind down the process of disinvestment.

The Fed's program of trimming its holdings was in full runoff mode until May 2019, with up to $30 billion in Treasuries and $20 billion being retired each month. After that, the Fed began slowing its pace of reduction of Treasury holdings to only $15 billion per month, and this Treasury reduction process came to an end in September 2019 as Fed holdings of government-backed bonds has declined to a less-than-desired level..Runoff of mortgage-related holdings continued along at a maximum of $20 billion per month.

The Fed prefers to hold only Treasury obligations in its portfolio, and so again shifted tactics again in October 2019, when they began to use inbound principal payments received from mortgage holdings to purchase new Treasurys, keeping its balance sheet the same size but rebalancing the mix of investments it was holding. This was a measured process. Redemptions of MBS up to $20 billion per month were to be used to buy more Treasurys, with any inbound funds in excess of $20B plowed back into MBS. However, with mortgage rates rising at the time, refinancing was virtually non-existent for much of 2019 and homebuying turned sluggish. As a result, the Fed stopped seeing MBS redemptions above $20 billion.

Although not meeting their goal to eventually hold only Treasury obligations and no mortgages in its portfolio, the Fed continued to state that it would not be an outright seller of MBS into the open market. This thinking seemed to be starting to change in this direction, and in its March 20, 2019 release, the Fed noted that "...limited sales of agency MBS might be warranted in the longer run to reduce or eliminate residual holdings. The timing and pace of any sales would be communicated to the public well in advance."

The process of slowly changing MBS holdings into Treasury holdings continued.

Novel Monetary Policy: QE Programs 2020-current

After the Great Recession QE (and other) response programs, the Fed would likely have preferred to never again need to use extraordinary monetary policy responses to prop up financial markets. It would likely have simply let its balance sheet slowly transform itself from a mix of Treasurys and mortgage bonds to one solely comprised of Treasurys over time, and seemed on a long-term path for this to occur.

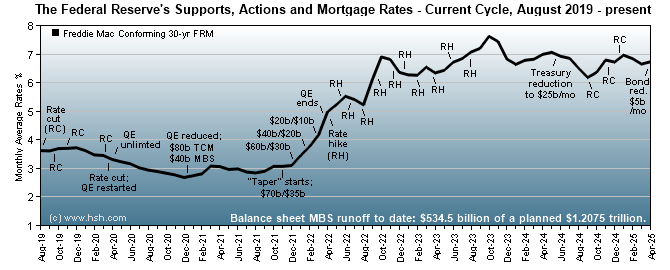

Then, in March 2020, the global COVID-19 pandemic hit. In short order, economies began to close down across the globe to deal with the spreading virus. Investors panicked, selling everything as fast as they could at any price if a buyer could be found. Financial markets were in an upheaval and there was a significant chance that a new (and perhaps worse) Great Depression might ensue. At the time, the Fed held about $1.37 trillion in mortgage-related instruments.

To address the market panic, the Fed not only slashed interest rates back to near zero, but also quickly restarted bond-buying programs. On March 15, 2020, the Fed announced that "over coming months the Committee will increase its holdings of Treasury securities by at least $500 billion and its holdings of agency mortgage-backed securities by at least $200 billion." Such was the panicky state of financial markets that it ran through these sizable amounts in a matter of days. Just eight days later, on March 23, the Fed simply stated that "The Federal Reserve will continue to purchase Treasury securities and agency mortgage-backed securities in the amounts needed to support smooth market functioning...". In other words, unlimited QE would run until markets calmed.

By June 2020, markets had calmed a bit. At the time, the Fed only noted that "over coming months the Federal Reserve will increase its holdings of Treasury securities and agency residential and commercial mortgage-backed securities at least at the current pace." Come December 2020, the Fed returned to specific purchase goals, noting that it would "increase its holdings of Treasury securities by at least $80 billion per month and agency mortgage-backed securities by at least $40 billion per month." These second QE programs pushed mortgage rates to what is believed to be all-time lows in January 2021.

With U.S. economy healing while the global economy sputtered in fits and starts, bond buys continued at these levels until November 2021, when a "tapering" process was put into place. At the time, it was expected that the Fed would gradually reduce purchases of Treasurys by $10 billion per month and by $5 billion for MBS, so that the wind-down process for accumulating new bonds would take about eight months, after which the first increase in the federal funds rate would occur. Given the experience of the last QE wind-down plan from 2018, markets expected to then see a period of portfolio reinvestment of inbound proceeds during a slow rise in short-term policy rates.

This did not occur. With inflation gaining speed and running well above the Fed's hoped-for levels, the central bank accelerated its tapering process to end months earlier than expected, indicating a earlier increase in the federal funds rate. It also surprised investors by revealing that there would be no period of reinvestment, and that balance sheet reductions would begin soon after the federal funds rate started to be increased. The first increase in the federal funds rate for this new cycle came on March 16, 2022.

Outright balance-sheet reductions began in June 2022, first starting with $30 billion per month in Treasury runoff and $17.5 billion in MBS runoff; after three months (September 2022) these figures were be doubled. In his prepared remarks at the time, Fed Chair Powell noted that "For agency mortgage-backed securities, the cap will be $17.5 billion per month for three months and will then increase to $35 billion per month. At the current level of mortgage rates, the actual pace of agency MBS runoff would likely be less than this monthly cap amount." In light of the Fed's 2019 stance on holding MBS, this seemed to imply that outright sales of MBS would be more likely sooner rather than later.

The Fed's holdings of mortgage debt peaked in April 2022 at $2.740 trillion. Rising mortgage rates curtailed refinancing activity and crimped homebuying, so the reduction in MBS holdings hasn't happened at the pace the Fed had hoped. By design, some $962.5 billion should have been trimmed from Fed MBS holdings by September 2024, but the decline has only been about $407.6 billion so far, far less than half of what the Fed was hoping to see. MBS holdings will decline faster as mortgage rates fall and refinancing activity picks up, but the Fed's present holdings are still at a level they thought would have occurred back in June-July 2023, so the process of MBS reduction is more than a year behind schedule.

Whether this eventually will result in a desire by the Fed to directly sell mortgage holdings to investors isn't clear. For now, there are still no official plans by the Fed to do so.

The Fed raised rates through July 2023, with the federal funds rate peaking at a 5.25%-5.5% level. After holding short-term rates at this level for more than a year, the Fed began a new cycle for monetary policy, cutting rates by a half percentage point in September 2024.

"Normal" vs. "Novel" Fed Cycles

Although the Fed rapidly lifted interest rates to about 22-year highs, the last and fairly brief cycle for rates (2022-2024) would be considered a "normal" cycle as it feature no extraordinary efforts to influence long-term rates, although there may be some residual effects from the previous "novel" downcycle for policy, which also included significant episodes of bond and MBS buying.

During "normal" policy cycles, the Fed makes changes to monetary policy by raising or lowering certain interest rates that it directly controls to retard or spur economic growth and inflation. Traditionally, changes are made to the federal funds and discount rates, but there are also new tools the Fed employs to tighten or loosen monetary policy, too. These include paying banks to keep reserve funds parked with the Fed (called "Interest On Reserve Balances", or IORB) or though a different, more complex method of swapping Fed-held debt for bank cash holdings (called a "Reverse Repo" agreement).

This latest "normal" cycle for monetary policy did feature rapid increases in short-term interest rates, and changes often came in extraordinary amounts, totaling 525 basis points in just 16 months' time, the holding there for another 14 month period. While the new downcycle for rates did start with a larger-than-normal 50 basis point cut, the path of cutting rates going forward seems likely to be one of a more measured pace, so it may take several years for monetary policy rates to return to "neutral". "Neutral" is currently thought to be a federal funds rate of perhaps 3% to 3.25%.

Volume, duration and velocity

Regardless of the tools the Fed uses to get there, interest rates will remain at elevated levels, at least compared to pandemic-era depths. The questions are, then, "How much will the Fed lower short-term rates?" (aka "volume"), "How long will it take them to get to their likely bottom?" (aka "duration"), and "How fast will they move them there?" (aka "velocity"). Obviously, for homebuyers, the final question is, "Where will mortgage rates settle as the process of lowering short-term rates continues?"

It bears noting that the Fed begins this downcycle for rates from a nominal rate level not seen for nearly two decades. It's easy to see now the impact that high interest rates have had on sensitive sectors of the economy, like housing or banking, but these difficulties are unfortunate collateral damage in the Fed's fight against inflation.

Homeowners, homebuyers and those in the mortgage market remember well the effects on the housing and refinance markets in mid-2013, when a spike in mortgage rates happened in the aftermath of then-Fed Chairman Bernanke's comments suggesting that the original QE plan would eventually come to a conclusion (the so-called "taper tantrum"). Starting in May 2013, average 30-year fixed rates rose by more than a full percentage point over a 10-week period.

History may or may not have repeated itself, but an absolute bond-market rout from the end of 2021 into the spring of 2022 lifted mortgage rates by nearly two percentage points, and this occurred before the Fed had made barely any change at all to short-term policy rates. As inflation spiked and the Fed kept raising rates in large blocks, mortgage rates moved up to more than 20-year highs late in 2022, dropped back for a time, and then resurgent inflation throughout 2023 pushed them to levels unseen since late in the year 2000.

Changes to the downside

It's fair enough to say that history is likely to be a lousy guide to the future, but it's all we have to go on to make judgments. Since the 1980s, there have been 12 Fed cycles for rates, both up and down. There have been periods of pretty pronounced increases, but decreases have been generally larger; for example, a downdraft from 1989-1992 saw a full 6.75 percent chopped off of the federal funds rate as it shrank from 9.75 percent to 3 percent. Other declines of similar size include a 5.875 percent cut from 1983-1986, and more recently, a 5.5 percent slide from 2000-2003. The most recent significant episode was 2006-2008, with a sizable total decline of 5.125, which at the time left rates at historically low levels. Since rates were already pretty low to begin with, the last cycle of rate decreases (2019-2022) was relatively small, totaling just 2.25 percentage points as rates were again pushed to the "zero bound" to combat the economic effects of the pandemic.

Changes to the upside

So much for the downside of rates. Given that interest rates had generally been declining for 40-plus years since the inflation-fueled days of the early 1980s, the Fed has arguably had some leeway in raising rates, since many of yesterday's "lows" were still elevated by historical standards. We have just endured the largest upcycle for the federal funds rate in recent memory during the 5.25 percentage point increase in 2022-2023, when the Fed set out to curtail inflation that had run to multi-decade highs.

Typically, the Fed has exercised somewhat more caution in raising rates when needed, with the second largest cumulative increase occurring from 2003 lows to 2006 highs, adding a total of 4.25 percentage points to the funds rate over that period. Other smaller cyclical increases of 3.875 percent (1986-1989), 3.25 percent (1982-1983) and a flat 3 percent in 1992-1993 have also occurred. Just before the pandemic, the 2015-2018 cycle of increases featured a total increase of just 2.25 percentage points, while the smallest increase of the bunch was just 1.75 percent from a 1998 low to a year 2000 peak during a very short cycle.

Average or typical "volume"

For the last 11 Fed cycles of rates (both up and down) the average cumulative move is about 4.125 percent. From the near-zero level where we started the last cycle of increases in 2022, history suggested that when the cycle of raising rates was completed, that the process would leave us with a federal funds rate of about 4.375 percent, all things considered. However, the worst bout of inflation since the 1980s saw the Fed push rates well above that expected level, so the most recent upcycle for rates was of a larger volume than has typically been the case over time.

Since the recent peak for the federal funds rate was only 5.25%-5.5%, it is unlikely that this new downcycle for the federal funds rate will approach the average cyclical decline of just under 5 percentage points, unless some unforeseen global episode or deep recession should form. Rather, and for the first time since perhaps the financial crisis and aftermath more than a decade ago, the Fed will likely try to simply get policy back to a "neutral" stance.

That said, the central bank does not know what the actual nominal level of a "neutral" federal funds rate should be, since it is not directly observable. Rather, determining whether policy is set too loose, too tight or just right can only be reckoned by studying various components of the economy over time.

At present, the neutral rate for the federal funds is thought to be perhaps 3.25% or so, and the Fed is now just at the beginning of its latest downcycle for policy rates. Starting this new cycle from a 5.25% to 5.5% target range, the Fed has already trimmed rates by 50 basis points in September 2024, leaving perhaps 150 to 175 basis points in cuts before the federal funds rate will be close to its expected "neutral" stance.

Average or typical "duration"

How long will it take the Fed to get us back to a typical or normal level for the fed funds rate? Again, history's not likely to be much of a guide, since the Fed will be responding to changes in inflation and economic growth as they come along.

If the total decline in the federal funds rate to get to neutral is perhaps 225 basis points, and there are only 175 basis points left to cut to get there as of this writing, it's reasonable to think that rates may return there quite quickly, perhaps only over perhaps a two-year time frame.

For much of its more modern history, and at least over the cycles we've tracked here, the central bank has generally preferred -- absent emergencies -- to make policy changes only at its regular FOMC meetings, held every six weeks or so. More often than not, it has even preferred a slower pace of increase or decrease, often making changes only at meetings where an updated Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) has been released (once each quarter).

Over the last 11 Fed rate cycles (dating to 1995), the average duration for a cycle overall was about 30 months. During that time, upcycles for interest rates were typically shorter, averaging 24 months before the next downcycle began. Downcycles for rates have tended to last somewhat longer, averaging 36 months before the next upcycle started. The most recent upcycle (March 2022-Sept 2024) was longer than usual, averaging 30 months.

So far in this new cycle, the Fed has not yet moved the funds rate back to a "neutral" level (neither lifting growth or damping it) nor even to one that is modestly restrictive, and so it remains at a moderately restrictive level. Although the Fed began this downcycle with a larger-than-usual 50 basis point reduction, there's little reason to expect that this cycle will proceed any more quickly or slowly than is typical.

Starting with the September 2024 cut, and if the Fed moves again to a cadence of cutting rates at each Fed meeting that features an updated SEP and trims rates a quarter percentage point at each of those meetings, the Fed funds rate would return to a "neutral" 3% - 3.25% range at the June 2026 meeting -- meaning this down cycle for rates would take place over a 22-month period, and rates would presumably then be held there for a period of time. If we assume a 36-month total downcycle, rates might remain at a cyclical bottom until perhaps sometime in 2027.

Of course, history's a poor guide to what may happen in the future. in its current incarnation, the Fed is inclined to adjust the federal funds rate as an accumulation of incoming data suggests it should, but there's no way of knowing in advance when the next financial market meltdown, disease outbreak, flare of inflation, recession or other global (or domestic) issue will show itself and require additional steps or a change in direction for monetary policy.

Average or typical "velocity"

The most recent iterations of the Federal Reserve policy-setting committees have all shown a preference for small changes in the Federal funds rate, usually a quarter-percentage point at a time, with a few half-point (or more) exceptions, most often on the downside.

However, after more than 20 years of increasing rates by no more than a quarter-point at a time, the Fed used a 50 basis point increase in May 2022, and then went on a four-meeting blitz of 75 basis point increases, backing down to a 50 basis point increase in December 2022 before returning to a quarter-point cadence as the funds rate approached its terminal rate for the cycle.

The Fed's velocity of increases in the funds rate during the previous upcycle was far faster than has been the case in recent Fed history. Even a single 75 basis point increase is uncommonly large, let alone four in a row, and it has been since perhaps the early 1980s when moves of this size were both common and frequent. Typically, large changes to the funds rate are most commonly seen to the downside, usually to address emergencies like the financial market struggles in 2008 or the COVID-19 pandemic.

The latest downcycle for rates started with an unusually large move of 50 basis points. It appears that the Fed's reason for doing so was to play a bit of catch-up, as annual revisions to labor conditions suggested that they weren't as tight as originally reported. It also may be that the Fed was looking to address the inadvertent additional tightening of monetary policy over time, as core PCE inflation had declined by more than half since its September 2022 peak. If the Fed holds nominal policy rates steady as inflation declines, the so-called "real" (after inflation) federal funds rate increases, adding additional drag on the economy. Whatever the central bank's reasoning for doing so, the new cycle started with a bang.

But what of the rest of the coming cycle? It's certainly possible that the Fed could continue to cut rates quickly. At present, however, conditions don't appear to warrant large cuts in rates, so a more typical quarter-point cut at measured intervals seems the most likely way this cycle will proceed. Of course, only time (and the incoming data) will tell.

What will happen to mortgage rates?

Is the history of fairly recent Fed moves any help here at all? Well, the environment in which mortgages are priced today is certainly different than in the past, so the experience taken from those episodes may not be all that helpful. However, the last time we had a federal funds rate at about a "normal" 3.25 percent rate (either precisely at this rate or rising or falling though it) was in September 2022; prior to that, similar crossings occurred in January 2008, May 2005 and August 2001.

The most recent period is arguably the least relevant of the group, as inflation was increasing and the Fed was rapidly raising interest rates. The currently-expected "neutral" rate of 3.25% in September 2022 was simply a brief stopping point on the way up, and was only in place for about five weeks. Thirty-year fixed mortgage rates were quickly pushing higher, too, averaging 6.11% for September 2022.

As monetary policy is now in a downcycle, perhaps the most recent time when short-term rates was falling to or through the currently expected neutral level is more indicative of what's to come for mortgage rates. In January 2008, the Fed was in the process of moving short-term rates down rapidly, and for that month, 30-year FRMs averaged 5.76%

The cycle just prior to that also saw the current expected 3.25% neutral-rate threshold crossed. Back in May 2005, short-term rates were in the middle of a multi-year rise. Even so, the average offered rate for a conforming 30-year FRM in May 2005 averaged 5.72%.

The only other time in our review of Fed cycles that a 3.25% federal funds rate was seen was back in 2001 -- August, to be exact, as short-term rates were being lowered quickly. At the time, 30-year FRMs averaged 6.95%

Interest-rate relief may be hard to find

Even as fixed rate mortgages should fall over time, they will likely remain expensive, at least when compared against the record lows so often seen in the aftermath of the Great Recession and COVID-19 outbreak. However, there may or may not be other lower-cost options for borrowers. Common Adjustable Rate Mortgages (ARMs) will of course be available in the market, but these may only be a slightly less expensive choice for potential homebuyers. Those looking for considerable interest rate relief will probably be disappointed.

In recent times, relatively few borrowers have chosen ARMs even when the break in rate is compelling. ARMs have made up only a fraction of loan originations in recent years, typically totaling in the high single digits to low teens in terms of market share outside of jumbos and non-QM products.

Initially in the last cycle, market-based long-term mortgage rates rose much more quickly than Fed-engineered short-term rates, but ARMs caught up over time. The difference between conforming 30-year FRMs and 5/1 ARMs for a time was reasonably wide, and a 5/1 ARM provided valuable rate relief for borrowers who could handle the risks that an ARM presented. As most ARMs end up on lender books rather than being sold to Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, there can be a large disparity of rates across a local market.

Among comparisons of the last few times short-term interest rates were at the expected "normal" level of perhaps 3.25%, only the 2022 period saw a significant differential between average offered rate for a conforming 30-year FRM and the initial fixed rate for a hybrid 5/1 ARM.. In September 2022, the gap in interest rate was 136 basis points, and so was unusually wide for a brief period of time.

More likely is the experience of the other three instances, where the interest-rate break was closer to a half point (27 basis points in 2008, 59 basis points in 2005 and 51 basis points in 2001, respectively). That's not a whole lot of interest rate relief, and doesn't move the "affordability needle" very much, either.

If you're unfamiliar with them, you might have a read through HSH's Guide to Adjustable-Rate Mortgages.

Wrapping it all up

In the last cycle, it didn't take the Fed very long to get the federal funds rate back to a "normal" level and surpass it. Although inflation has cooled and the economy and labor markets have settled down, it may take a while to get us back down to the expected new "normal" for the federal funds rate. This will most likely happen over a period of perhaps two years, and once there, if history is any guide, it may remain there for a period of time.

To be fair, even 6 percent fixed-rate mortgages are still historically quite good but also feel expensive relative to the record-low bottoms and near-bottoms for rates we became accustomed to during the extraordinary times of the financial crisis, post-"Great Recession" and pandemic era for interest rates. In fact, the average rate for a conforming 30-year fixed rate mortgage over the last 30 years is actually 5.56%, and there's at least some reason to expect that mortgage rates may end up somewhere in this range over time, at least as long as the economy is growing, inflation remains tame and Fed policy rates remain near "normal". That's not to say they can't go lower, or higher; average rates of course for any given period are made up of both periods of higher and lower values.

The future

The good news is that mortgage rates are already well below their cyclical highs, having peaked in late October 2023 at 7.79%, per Freddie Mac, and an improved inflation outlook should keep them from revisiting those levels anytime soon. At the same time, it is true that investors often rush to one end of the see-saw and push market-based rates higher than they ought to be given economic conditions, and also true that they often rush to the other end, at times pushing interest rates lower than they ought to be. We have likely seen some of this behavior again, with mortgage rates falling as much as 170 basis points from 2023's peak at one point -- even as the Fed had yet to even make a single move -- before backing up again.

Looking forward, if you're thinking of buying a home in 2025 or beyond, it might be a good idea to use perhaps a 5.5% to 6% percent interest rate for 30-year fixed rates in your calculations, at least based on the cycles we've evaluated. That's not to say it will be a smooth ride down to those levels, but rather that's where they may settle over time. Absent economic calamity, global emergency or garden-variety recession, it may be hard to expect mortgage rates to get a whole lot lower than that.

If you plan on selling a home in the next year or so, keep in mind that still-high mortgage rates means affordability for buyers is remains limited, especially if there are no viable lower-cost mortgage products for buyers to turn to. As such, over time you may not have as much pricing power as you have had in recent years, or at other times when mortgage rates are lower.

For more about the Fed and mortgage rates, see our post-Fed meeting analysis. For updates on market conditions and mortgage rate trends, see HSH's weekly MarketTrends newsletter and for mortgage rates forecasts, check out our Two-Month Forecast for mortgage rates.

Related reading: