April 6, 2020

Preface

Things were looking up for the U.S. economy before the spreading coronavirus caused a government-mandated shutdown of activity. The wreckage of the U.S. and now global economy is just starting to be reflected in truly astounding statistics: hundreds of thousands across the globe are sick, tens of thousands are dead and literally 10 million people in America lost their jobs in just a two weeks' time, with more yet to come.

The unprecedented suspension of economic activity and dysfunctional financial markets has seen the Federal Reserve open the credit spigots as wide as they ever have been, perhaps wider, and the federal government pushed out a $2 trillion "phase 3" set of fiscal supports to keep what will be a nasty recession from turning into something even worse. More supports may yet be needed.

The combination of these actions served to at least stabilize financial markets, so the plumbing of Wall Street is functional, but Main Street is a ghost town. Millions of small and micro-businesses are in danger of disappearing if we do not soon find a way to get them either opened or better supported very soon.

Mortgage markets are mostly functioning, with the QM/conforming space well supported by the Fed's pledge to purchase unlimited amounts of mortgage-backed securities. The Non-QM and jumbo spaces -- private money -- are wholly or partially shut at the moment, as few investors are interested in making funds available into markets that have no form of guarantee of return of principal, let alone interest. This is especially true at a time of an increasingly shaky household sector from income disruptions, and perhaps more so given the "no-doc" forbearance offers for government-backed mortgages. Although there is no current specific credit facility to support them, mortgage servicers must still make payments to investors in mortgage that are subject to forbearance, and there is a growing risk that some of these servicers may become insolvent as a result.

With bleak economic numbers just starting to be seen, and warnings of some truly awful (but hopefully peaking) figures tracking the spread and effects of COVID-19, there is little doubt that we are headed into some even more difficult times over the next couple of months, if not beyond.

Recap

To say that our last forecast was only "way off" would be an understatement. Like plenty of others, we failed to recognize the speed with which COVID-19 would disrupt things, first collapsing global supply chains and then causing hard lockdowns in countries and regions around the globe. In January, we were cautiously optimistic that the Fed's actions of 2019 and the cessation of trade wars would put economic growth on an upturn; data from January and even much of February supported that outlook, with strong employment gains and some pickup in the long-beleaguered manufacturing sector. Housing markets were solid, and the new home market was starting to show some of its best numbers in more than a decade. Consumer spending was good, and all signs pointed to at least a mild acceleration in overall GDP growth from around 2% to something closer to the mid-to-upper 2% range. And then the bottom fell out.

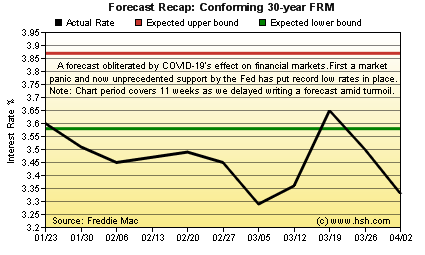

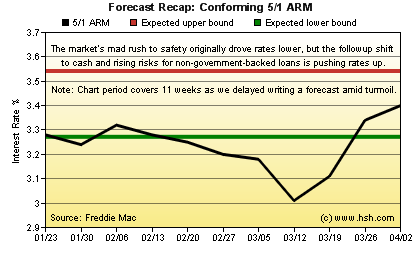

In January, we thought we would see the average offered rate for a conforming 30-year FRM run in a range between 3.58% and 3.87%. Even including two extra weeks in the review period (we held off writing a new forecast due to turmoil) we managed to land in that range in only two of 11 weeks, as rates cascaded to "all-time" lows during the period, with a low value of 3.29% and a high mark of 3.65% tallied. The first move into our expected range came at the beginning of the period; the other came amid a crush of refinancing and a mad rush of "sell everything and go to cash" by investors that necessitated urgent Fed action. For the initial fixed rate for Hybrid 5/1 ARMs (not that many care in this low-rate climate) we thought we'd see rates wander between 3.27% and 3.54%, but they actually posted a 3.01% bottom when investors first rushed to Treasuries and 3.40% high late in the period when recognition of risks shifted.

As far as forecasts go, the last one was far from our finest moment. The good news is that we erred to the upside, and that was to the benefit of both homebuyers and homeowners, at least until about mid-March. How these audiences will act in the days ahead remains to be seen, but it's reasonable to think that a lot of refinances and homebuying have been interrupted due to job loss, stay-at-home orders and social distancing.

Forecast Discussion

As we write this, is hard to gin up much enthusiasm for the outlook. We are just starting to see unprecedented job loss. Trillions in stock-market losses have changed the financial picture for millions of Americans. Herculean and heroic efforts by first responders and the medical profession to manage the outbreak are in full view but there is not yet much if any light at the end of the tunnel, really just more hopes that positive numbers at present. As is almost always the case, government help is coming, but amid a good deal of confusion and will be late to arrive.

There is great uncertainty about what may come in the next two months, and without knowing how much control over the disease can be exercised it's difficult to have any sense of how much performance can be expected out of a now-crippled economy. As such, we'll limit our focus to what exists now in terms of fiscal and monetary policy. First, the Federal Reserve's move with unprecedented speed to slash the federal funds rate back to near zero and re-start QE-style buys of Treasuries and Mortgage-Backed Securities in unlimited quantities (among other credit and liquidity facilities) will keep both market interest rates and mortgage rates low and reasonably stable through the period.

In March, a surge of refinance activity overwhelmed lenders, who began to price defensively so as to better manage the inbound flow of business; this surge is working its way though the various pipelines, if at less-than-normal speed, but will eventually be sated. Pipeline issues solved, lenders will again begin to pass along lower mortgage rates to consumers without demand-tempering premiums in the day ahead.

But will consumers respond to lower rates? Can they? It's not yet clear if the government-mandated recession will hit homeowners or homebuyers harder. There are far more homeowners than potential homebuyers, so to the extent that millions of homeowners have moved to the ranks of the unemployed, opportunities for refinancing will be little more than a mirage. Potential homebuyers (even those who remain employed) were already facing difficult markets this spring, as again-rising home prices amid sharply limited supply of existing homes to buy meant challenges in finding what they need or want (or could afford), regardless of how low mortgage rates might be, and to a degree, lower mortgage rates only tend to make this worse by incenting new buyer demand. Now, given stay-at-home orders and the difficulty of buying and selling homes during this time of social distancing, who would want to sell their home, knowing they would have to then move into these challenging markets to find their next place to live? Even if they do list them, how many potential buyers try to buy homes they cannot visit in person or will be able to conduct a fully hands-off transaction? Some, maybe, and investors perhaps, but odds favor fewer buyers rather than more.

It seems to us that the combination of these items suggests that while there will be plenty of supply of mortgage credit available as we move into the spring, we may not see a commensurate increase in demand. In turn, this would tend to put additional downward pressure on mortgage rates.

We know that the federal government is putting into place the CARES Act, which will loose some $2 Trillion into the economy over time. Everything from $1,200 checks to individuals, expanded and newly-generous unemployment benefits and mortgage relief and plenty more were included. That said, eventually having money flowing in this fashion likely only helps people manage the obligations they have, but isn't specifically targeted to be newly spent to stimulate economic growth... and even if it was, encouraging spending in ways that produce the best benefit might prove difficult, what with stay-at-home edicts in place and so many businesses that would welcome the chance to serve clients closed by fiat. All this taxpayer money will of course help at some point, and in some ways... but who knows in what ways? If the vast majority of people simply choose to bank inbound funds for a rainy day or use them to trim down credit card balances there will be almost no economic benefit from them, so growth-boosting will have to come from elsewhere.

Of late, discussions are afoot for a "phase four" set of stimulus, most likely aimed at infrastructure spending. That's all well and good, but if we learned anything from 2009's trillion-dollar ARRA, shovel-ready projects really don't exist and the process by which the federal government allocates funds can mean it will take a long while to have much by way of effect. Fixing roads and bridges is certainly fine but only goes so far; one might quip that given the "work from home" first reaction from government that roads and bridges might not be a first priority, but that the money should probably go to shoring up the electrical grid and ensuring internet access across the country.

But we digress. Taxpayer-funded stimulus will help the economy, but its effects are unpredictable and certainly not light turning on a light switch. Even if things began to improve markedly over the next nine weeks it would be insufficient to lift interest rates by much, if any. From where we sit, the economic shutdown seems likely to end (whenever it does) with a whimper, not a bang, and when it does return, slow growth and associated weak economy-wide demand for credit will continue to keep downward pressure on interest rates in general.

Forecast

We'd like nothing more than to be writing a "mortgage rates expected to rise amid strong economic growth" kind of outlook for the next nine-week period, but that just doesn't seem in the offing. As we write this, mortgage rates are just a hair above record lows set back in early March, and the prospect of new records being set in the weeks ahead are pretty good at the moment. Although periods of either stress or even temporary ebullience in financial markets could push rates up at times, the general outlook to us seems as though lower is the order of the day.

For the next nine weeks, we think that the average offered rate for a conforming 30-year FRM as reported by Freddie Mac could go as low as perhaps 3.10% but probably won't move up much from here if at all, so a top figure for the coming period would be perhaps 3.45%. For the initial rate on hybrid 5/1 ARMs -- products that are often not sold to Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac -- its likely that deterrent pricing will persist for a bit, so we might see perhaps a 3.15% to 3.50% range for the most common ARM over the next nine-week period.

All that said, and while we're willing to venture a guess as to what may happen with mortgage rates, we make this forecast without much conviction. Conditions remain "fluid", as the phrase goes.

This forecast expires on June 12, 2020. From where we are at the moment, it's hard to look forward and have a sense of where things will be economically, but we will be heading full tilt into summer at that point, so that's at least a positive to focus on. Warm, sunny days will perhaps bring growing optimism about the road ahead, and when we get there, we hope that this forecast came out better than the last. Stop back and see.

For interim forecast updates and market commentary, see our weekly MarketTrends newsletter.