What's holding back the housing market this spring?

With the advent of spring, the traditional homebuying season should be fully underway. But is it? Not so much.

Spring traditionally plays host to hordes of eager homebuyers for a few reasons:

There tends to be some pent-up demand fostered from the colder, slower winter months when fewer people tend to shop for homes

Parents are eager to shop for and find homes in the late spring/early summer to make the transition to a new school as easy as possible

Listings pulled from the market during the holidays are re-listed, and other potential home sellers are more likely to list their homes to capture both increased buyer traffic and the seasonal upturn in home prices

But housing markets continue to endure considerable headwinds from both the demand side and the supply side. Some of these issues are fairly recent occurrences; some have been with us for years already, while still others were years in the making. The question of course is what, if anything, can change the situation meaningfully? The answers aren't clear or straightforward, but let us first look at the challenges in the market today. These aren't in any order of importance, as each may affect a potential buyer to a greater or lesser degree.

Mortgage rates are painfully high for many borrowers.

Mortgage rates are high, it's true. There has been at least a homebuying generation or two since 30-year fixed mortgage rates routinely ran in the 7% range, let alone the near 8% peaks seen at the end of 2023.

But the truth is also that the housing market has seen -- and even performed well in -- periods where mortgage rates were at present levels. Mortgage rates themselves aren't specifically the issue, but when combined with record- or near-record high home prices, they are a component of the troubles potential homebuyers face.

At least part of the issue with today's rates is perception. Before the run-up in rates, mortgage rates had been below or well below what might be considered "normal" levels for most of the past 15 years. If mortgage rates had risen from their near-record low 3% range to something only in the 5% area, rates would have been considered to be high but would actually more likely have been closer to long-run normal levels. Importantly, they wouldn't be high enough as to cause the kind of stumble in the housing market we've seen and are still seeing.

The good news (of sorts) is that when mortgage rates eventually return to those 5% "normal" level they will look relatively cheap to homebuyers who have endured today's lofty levels. This will also allow any new homeowners who successfully navigated today's high rates to refinance and help lower the cost of owning their homes.

As well, at least one part of the market isn't (or is less) affected by today's high mortgage rates -- cash buyers or buyers who only need a small mortgage amount to cover the purchase of a another home, such as a homeowner looking to downsize.

However, this leads us to the next issue.

The are few available, desirable or affordable houses to buy.

While the inventory situation is improving slowly, it remains a serious problem.

You might think that the limited supply of homes for sale is a recent phenomena, but you wouldn't be quite right. Although intensifying since the pandemic, the issue of thin inventories of existing homes for sale has been with us for many years now.

At least in general, the National Association considers six months of supply of homes at a current rate of sales to be optimal. Five months would likely be considered ample, and perhaps four or so sufficient supply to meet typical demand. The problem is that supply has run for years now below even the "sufficient" level, and at times has been as lean as 1.6 months of supply (January 2022). Here are some facts about the issue:

Outside of two months in the beginning of the pandemic shutdown, and a string in the middle of 2024*, there hasn't been four months of existing home supply on the market since September 2019... more than four and a half years ago.

Five months of supply? You'll have to travel back nearly nine years, since it was August 2015 the last time inventories were that thick.

For "optimal" levels of six months of supply? Nearly 12 years have passed, and back in 2012, the housing market was still dealing with the effects of the housing market crash and Great Recession. Rather than a surge of supply, this wide ratio was more the result of a lack of buyer demand at that time.

* A caveat about the inventory-to-sales ratio: This figure can rise even if no new for sale homes come onto the market. All it takes is for the number of homes available for sale to hold at a relatively constant level while actual sales slump. That was the case in mid-late 2024, as existing home sales slowed to a annual pace last regularly seen about 30 years ago.

So the issue of little "available, desirable and affordable" to buy has been with us a very long time now. It's just gotten worse over the last few years.

Part of the issue is that it's hard to add meaningful supply where it is most needed. Much significant new construction takes place far away from densely populated cities and so doesn't do much to alleviate the housing shortages in inner-ring suburbs -- exactly where pandemic and post-pandemic demand has been most pronounced.

Another factor in the lack of supply comes from what is called the "lock-in trap", where a homeowner isn't willing to give up a low-rate mortgage to move to a new, more expensive home with a higher-rate mortgage.

While this may be the case, consider for a moment though that this issue may go beyond a simple mortgage interest rate: It may be that a homeowner who qualified for a $300,000 mortgage at 3% a few years ago may not be able to qualify to buy a new home with a $400,000 mortgage at a 6.5% rate. It may not be a reluctance to sell and move but rather an inability to do so that is keeping many homeowners put.

Consider also that someone selling a home usually needs to find another in which to live. In this way, sellers are also confronted by the issues of little available to buy and high prices even if they can qualify for a new, larger mortgage amount and higher interest rate.

There are some offsets to these issues, albeit imperfect ones. A seller may be moving to a newly constructed home or relocating to an area where inventory levels are better, so the supply issue might not affect them as severely. As well, high home values may mean a seller has a deep home equity position, which may mean a larger downpayment for the next home and a smaller step-up in loan amount to cover with a new, higher rate.

Related: Track home value changes in more than 400 housing markets

Home affordability makes buying difficult.

And here we come to the crux of the problem. While mortgage rates have certainly been this high before (and at times, more than two-and-a-half times higher than today, in fact) median existing home prices have never been this high.

While hardly "the good old days", the last time 30-year fixed mortgage rates were routinely around the 7% mark was August 2001. At that time, the median price of an existing home was $154,700 -- and the median family income in the U.S. for all of 2001 was $51,410. At a 7% rate, that's enough income to qualify a borrower for a $140,177 loan amount (excluding the effects of any debts, taxes or insurance costs on qualifying). This amount plus a 10% down payment ($15,470) would be sufficient to qualify for a home.

Today, the median price of an existing home sold in January of 2025 was $396,900; the median family income through 2023 was $96,400 (latest Census estimates), and even adding a 4% adjustment to income for 2024 only brings the income to $100,257 as a working estimate today. At a 7% rate, this current income would only qualify a borrower for a $287,478 loan amount (also excluding the effects of any debts, taxes or insurances on qualifying). This amount plus a 10% down payment ($28,748)... would still leave a gap from the median home price of nearly $80,374.

It is the combination of mortgage rates and home prices that can enhance or erode home affordability, and today's toxic combination of 20-odd year highs for mortgage rates and near- or at-record home prices has crushed affordability. Even when homes do become available to buy, many are simply too costly for many wanna-be homeowners, and we've all heard stories about prices being bid up to levels way over asking price in some markets.

On a "pass/fail" basis relative to the family income needed to purchase a median-priced existing home -- and factoring for tax and insurance costs -- just 42% of the to 50 metro housing market registered a "pass" in the fourth quarter of 2024, so 58% of the most populous 50 housing markets are unaffordable in the aggregate.

Since we're using 2001 -- the last time mortgage rates were routinely at about 7% -- here's something worth considering as a reference.

To make today's prices as relatively affordable as 2001 (theoretically) was, and by our calculations, mortgage rates would need to be about 3.64% or home prices would need to be not more than about $272,190.

Of course, neither component is close to those levels, and of the two, it's more likely that mortgage rates return to 3.64% than home prices dropping to those levels. We saw the damage that a significant decline in home prices can do not all that long ago, and few would want to go through that again.

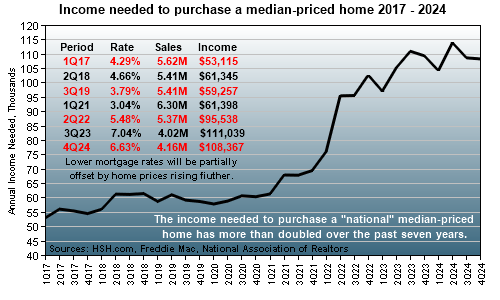

The affordability situation has only significantly worsened in recent years as the run up in home prices coincided with the run up in mortgage rates.

|

Related: See the income needed to purchase a median-priced home in each of the top 50 metro areas

Distortions from the last housing crash

The last housing market boom and bust created some durable distortions in the housing market. We think this is an unappreciated factor in today's housing climate, and likely an important one. Perhaps an winding anecdote might help explain it best.

Let's say a young couple bought a starter home back in 2005, with intentions to expand their family and then trade up when the kids were closing in on school age. The market was white hot then; sales of existing homes tallied over 7 million for the year (and another 1.3 million brand-new homes were sold, too).

Time wends forward. By late 2007, the housing market starts to crumble; by 2008, it has collapsed to roughly today's sales rate, believe it or not -- about 4.12 million units, give or take a little. Financial markets and the economy turn down, banks and mortgage lenders fail, the Fed begins emergency rescue plans, Fannie and Freddie become wards of the government. Home values plummet, unemployment rises.

Time wends forward. It's now 2010. This young family now has a home that's considerably underwater. One of the couple loses their job. They start to have trouble making mortgage payments and are lucky to receive a temporary HAMP loan modification to hold onto their home. The original plan to trade up before the kids start school is now history.

Time wends forward. It's now 2012. A new job has re-appeared, the mortgage is again current. A refinance under the HARP plan has provided a chance to lock in a then-record low rate and be able to remain in the home, which is still a fair bit underwater. This family's not going anywhere.

Time wends forward. Now 2015, the home has recovered all the value it lost, and with payments now made for nearly 11 years, there's actually enough equity available to use for a downpayment on another place. However, after years of being a mess, the couple's finances are finally solid again, and taking on huge new debt doesn't seem like a great idea. Maybe a renovation, turn the basement into living space, add another bathroom? Meanwhile, the oldest child is now in middle school and the youngest in grade school, the family has become enmeshed in the neighborhood and school systems, and the house and community feels like home, and though the space is smaller than optimal, they've made do with it. Stay and renovate it is.

Time wends forward. It's 2018. High school's starting for one child, middle school for another. Renovation has improved the small house issue, so not going anywhere for now; college for one child is just a few years away anyway, so makes no real sense to trade up now.

Time wends forward. Now 2020; pandemic breaks out. Everything a mess. Crowded house situation worsened by everyone home! Job losses everywhere, and life in general in upheaval. Although updated and living space expanded, the couple has now been in the "starter" home 15 years. With everyone home, they could probably use more space but everything uncertain, and not a great time to make changes.

Time wends forward. It's 2023. Home prices have gone up by more than 50% since early 2020 and mortgage rates have more than doubled since 2022. Even if they wanted to buy a house, there's little available or affordable. One child now in college and the other right behind. House emptier much of the time now. Move up? No... but maybe they'll downsize in a couple of years... if housing market conditions permit. If not, they can stay, since the starter home has plenty of space for two... and so on.

It's a long way around, to be sure, but the outline above is just one potential path of distortion with its genesis in the last housing boom and bust. There are literally millions of other stories, including folks who for myriad reasons failed out of the homes they owned and weren't eligible for new mortgages until the mid-part of the last decade and have since been adding more demand into the market. Of course, none of this even considers the so-called "lock-in effect", where homeowners holding low-rate mortgages are loath to give them up.

According to Redfin, homeowner tenure (length of time in a given home) peaked back in 2020 at about 13 years, a then-doubling of the length of ownership seen back in 2005. While this time has settled back to just under 12 years recently, it still is a historically long tenure period. The National Association of Realtors current estimate of the ownership period still 13 years, up from about 10 years back in 2008. Regardless of the source, these lengthy hold periods mean that normal or typical "churn" in the existing home market remains distorted. Given the challenges today's first-time homebuyers have had just getting into a home, it seems unlikely that they will be willing to jump ship very soon, either.

The distortions of the last housing bust didn't only affect the existing home market. Did we mention that many home builders failed after the last boom and bust, and that new housing creation failed to keep up with demographics for years? Back in 2021, Freddie Mac estimated that there was a shortage of 3.8 million homes, and home building has only recently began to start to make a dent in that deficit. However, new home construction isn't a perfect or even optimal replacement for existing homes, since much large-scale tract construction takes place at greater distances from center cities and often at higher costs.

We could go on, but suffice it to say that the last housing boom of about 20 years ago and the bust of about 15 years ago produced lasting distortions that are affecting the housing markets in myriad ways today.

So what's the magic cure for what's holding back housing?

There really isn't one... except time. In previous times when the housing markets came to a relative standstill (and they have before), private markets have stepped into the fray, for better or worse.

Mortgage rates in the high double digits? Adjustable Rate Mortgages (ARMs) emerged, offering lower rates today and the potential for lower rates in the future.

Traditional ARMs turn out to be troublesome? How about a fixed-rate balloon-reset mortgage? Hybrid ARM with fixed rates up to 10 years, 2-1 buydowns, 40-year terms, PayOption ARMs and countless other innovations?

Those private market innovations -- some which were highly successful at their time (TwoStep/Balloon Rest Mortgages) but faded, others have hung around for decades (Hybrid ARMs, etc.) are not in the cards to help unclog the housing market. The mortgage playing-field changes from Dodd-Frank and other regulations has kept private markets on the sidelines since the last housing crash, and Fannie and Freddie are still wards of the government.

Desperation may breed creativity, and in different times likely would have by now, but innovation in mortgages came to a halt years ago and isn't likely to return anytime soon. Banks aren't and haven't been very engaged in mortgages for some time, and actually often step out or back from mortgage markets when difficulties emerge (either through tighter lending standards, eliminating mortgage choices from their menus or exiting altogether). Mortgage banking firms rule the markets today, but without robust private secondary markets in which to sell unique or innovative mortgages, most simply make loans for sale to Fannie or Freddie or perhaps to a willing correspondent, as might be the case for jumbo mortgages.

So, time it is. Over time, the housing market will likely see borrowers with gradually increasing incomes, allowing them a chance to catch up a bit. We'll also see gradually falling mortgage rates, which will help to extend affordability a bit more each time they meaningfully decline. The supply of new homes will eventually fill in some of the yawning gap in actual supply, and home price increases will throttle back and flatten, probably something closer to the inflation rate or even below it (should supply improve measurably).

"How long?" you ask? There's no simple way to know the balance point, but we'd suspect that for sellers to sell and buyers to buy that 30-year fixed mortgage rates will need to move closer to long-term norms (somewhere around 5%). Home prices will need to level off, and hopefully not at levels much higher than today's, and affordability will need to move back to levels that are at least closer to normal than the sizable gap described above.

A final note: If you're thinking that difficult housing markets are a new thing... they aren't. The origin of this article came from a March 31, 2014 MarketTrends titled "With Rates Fair, What's Holding Back Housing Markets?" In it we noted: "The litany of possible sale dampeners is long: A lack of inventory to buy. Higher prices and higher mortgage rates causing reduced affordability. Underwater homeowners who can't or won't sell. Tight lending standards. High debt loads, including student-loan debt. A poor job market. Weak income growth. Residual fear from the crash. Ineligible borrowers due to foreclosure... and even folks who refinanced at rock-bottom rates and now don't want to give up the lowest rate they'll ever get. There are probably others, too." Do any of the issues described in that paragraph sound familiar?

After we wrote that MarketTrends, it took about four years before housing markets finally started to look fairly normal; here's hoping for a speedier resolution this time. Of course, the more things change, the more they stay the same.